Vignesh Krishnan, Ngawang Lhakey and Isha Thakur

Background

COVID-19 and the prolonged school closures across the country have had a catastrophic effect on the learning of children. More than ever, there is a widespread focus among the social purpose and multilateral organizations, state and central governments, and educational institutions, on bridging the widening learning gap in children. The focus on foundational numeracy and literacy in the New Education Policy 2020 and the subsequent implementation of the NIPUN Bharat Mission are all indicative of the shift from schooling to learning. However, the genesis of the discourse on learning outcomes can be traced back to over two decades of work led by Pratham, a non-governmental organization operating in the space of school education.

How does one make sense of the story of Pratham? Let us begin with the story of Kaajal, a young girl who migrated to Delhi, leaving behind quiet village afternoons, in search of new beginnings. When Kaajal moved to Delhi in 2006, she was far behind the students of her age. Kaajal was fortunate to join one of the Pratham libraries, set up in an urban slum in Delhi to provide access to quality resources and aids for children from disadvantaged communities. Over the course of a few months, Kaajal showed immense growth in basic arithmetic, English and Hindi. Underlying this story is the fact that millions of children, in both rural and urban parts of the country are far behind attaining foundational numeracy and literacy skills. Pratham as an institution saw the urgent need to measure learning outcomes to get reliable data on children’s learning. Quite early in their journey, Pratham developed a simple tool to assess the reading levels of the children they served. Over the years, it was clearly evident that although children went to school, they were not learning well. This led to the birth of the Annual State of Education Report (ASER), a nationwide household survey conducted to assess the reading and arithmetic levels of over seven lakh children from 15000 villages across the country.

ASER has been one of the most significant initiatives by any non-governmental organization in the field of education. While it started as a survey to assess the learning levels of children, ASER over time has shaped the nationwide discourse on learning outcomes and the impact on children in India.

ASER’s participatory approach to generating evidence

Every year ASER Centre generates the ASER village list from the village directory of the Census 2001. The volunteers first go to the assigned villages, collect basic information on the village as a whole and then choose 20 households in each to survey. The team engages with community members through a series of conversations about the village, the school, their children, and education. They collect basic information about the household (e.g., number of residents, information about assets) and more detailed information about each child living in the household. All children irrespective of their gender and status of their schooling (dropped out, never went to school, government, private, religious, anganwadi, or any other institution) between the ages of 3 and 16 are tested one-on-one by the survey team). The surveyed group of children take the reading and arithmetic assessments that are organized in the form of simple to complex tasks. In addition to the assessment, one government school per village is also surveyed.

Each year, thousands of volunteers conduct the surveys over an intense two-day time period in almost all of India’s rural districts. ASER then compiles all the collected data into a large database, which is randomly rechecked as a quality control measure. An example of this includes calling the people listed in the household survey forms to double-check that the volunteers did indeed survey their homes. After a rigorous quality check, the data are compiled into state and national level reports.

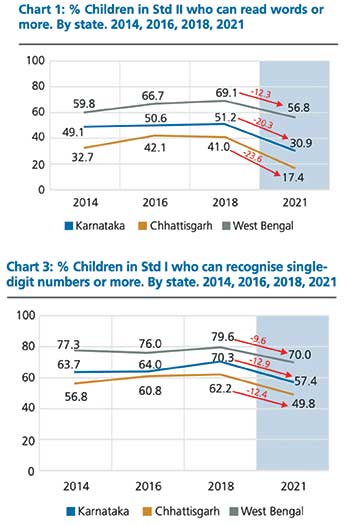

ASER 2021 however focused on four main areas: Identifying school enrollment patterns, incidence of tuition patterns, availability of and access to smartphones/learning materials and support for learning at home. The COVID-19 crisis made it impossible to conduct a nationwide 1-1 reading and arithmetic survey in 2020 and 2021. However, ASER found opportunities to conduct the learning surveys in three states (Karnataka, Chhattisgarh, and West Bengal) across three different time periods between late 2020 and early 2022.

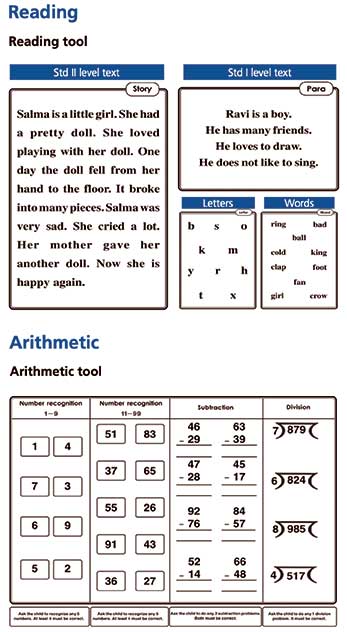

Assessment Tools |

ASER’s journey and its impact over the years

The annual conduction of ASER and the widespread dissemination of its results at the national, state, district, and sub-district levels using simple indicators matter because it allows for “reflection” that is essential for change. ASER’s data generated with speed and predictability has undoubtedly demonstrated the possibility of using simple, reliable and scientific methods of sampling and assessment on a large scale to bring the government attention of the discussions and debates on the topic of children’s learning and education to its national agenda. This stands in contrast to the time of ASER’s conception in 2005 when there was plenty of data available on schooling, with most people, from parents to government functionaries concerned with getting children into school but none that focused on the issue of their learning, let alone conducting any estimates thereof.

ASER’s simplicity easily enables a broad cross-section of people, even semi-literate parents, to look closely at children’s learning and see the problem in a simple way. ASER 2005, released in January 2006 marked the first time the nation learned of district-level independent estimates of children’s mastery of the basic skills of reading and arithmetic and many were shocked when it showed that only about half of the children enrolled in grade 5 could do arithmetic expected at Grade 2 level and that half of all children who had spent five years in school still could not read at a Grade 2 level. Significant findings as such were reinforced year after year across the country, whether in public or private schools.

Clearly, even though India has made impressive strides over the last couple of decades after spending crores of rupees on delivering a Right to Education and universal enrollment with “schooling for all”, the rate of development is not encouraging and is one that merits serious reflection on the part of policymakers. There was a sense among teachers and practitioners, that what was happening in the schools and how much “value” was being added to the child’s capability each year they continue in school was not satisfactory. It was clear that India needed to shift attention away from inputs to outcomes and as a direct result, ASER has succeeded in bringing children’s learning to the center stage of debates and discussions on education and de-mystifying the learning crisis. From the focus on “every child attending schools” along with the provision of adequate infrastructural and teaching facilities, the debate has now moved to “every child learning well” where inputs are assumed, but the interest is in outcomes. Following this, it has been successful in catalyzing the shift towards making foundational literacy and numeracy a part of the National Education Policy 2020 broadly and more specifically calling for more educational measurement, timely analysis, and evidence-based planning by the government. ASER has been cited in major Government of India documents such as the Approach Paper to the XI and XII Five Year Plan, the Economic Survey of India and in the Education Chapter of the XII Five Year Plan. ASER Centre has also been invited to present its data and findings to state ministers and secretaries of education on several occasions.

Once the assessment has made the problem visible, then the engagement to transform it into actions could begin to flow. ASER has led to a lot of discussions nationally and internationally, with enormous routine media coverage about where children’s learning is, how it can be measured, and how they can be supported to make progress. Many large-scale learning assessments with tools very similar to the ASER’s are being conducted regularly by the central and state governments. For instance, there is the National Achievement Survey (NAS), conducted by NCERT, a central government institution, every few years with children in grades III, V, and VIII, and most states/UTs conduct their own State Learning Achievement Survey (SLAS).

Status of Learning during the pandemic across 3 states |

Solving the learning crisis: Evidence to Action

Taking into account the ASER reports, some states are implementing programs aimed at improving learning outcomes. Given the reality of the usual way of teaching the curriculum using the prescribed grade-level textbooks instead of teaching the children in India, as ASER data corroborates, it means that many children get stuck and left behind even at a young age. So then, how could we structure the teaching-learning activities to improve learning outcomes? An innovation to demystify this learning crisis and design a pathway to a solution in this context is Pratham’s “Read India Program” that uses rigorously evaluated methodology of “Teaching at the Right Level” (TaRL) pedagogy and “Combined Activities for Maximized Learning” (CAMaL). In partnership with nine Indian states, it is practiced across many districts and requires only reorganization of time and existing resources. Schools and villages reorganize themselves for a few hours during the normal school day and children from different grades who are at the same level of reading ability or at the same level of knowledge are grouped together and taught. The doable new approach has been found to be effective in many settings in India with estimates of approximately 6.3 million children having reached through these partnerships. Such work that starts with the ASER assessment can also provide large-scale solutions for the learning crisis faced in many parts of the developing world as well.

The ASER model’s simplicity coupled with the rigor of its sampling methodology and low cost is increasingly being recognized on global education platforms as it makes for an interesting option for many countries with contexts similar to India. Pakistan has its own ASER, East Africa calls it Uwezo, Mali’s named it Beekungo and Senegal calls it Jangandoo. In Laos, the historical reliance on the Early Grade Reading Assessment (EGRA) for The Pencils of Promise (PoP) students has been replaced with ASER owing to a much better fit. The 14 countries within the People’s Action for Learning (PAL) Network, established in 2015 with its headquarters in Nairobi, Kenya, use the ASER model and collectively test more than one million children every year.

At a micro level, ASER’s simplicity has seen an impact in de-mystifying learning for the parents and making them a part of their children’s learning journey, the majority of whom, especially mothers are illiterate or non-schooled. They understand the importance of “schooling” but do not feel they can understand “learning” and what it entails or how they can support their children’s learning, leaving it entirely to the experts and educated people. The results from ASER, however, are easy to digest for it is their children and the children of their neighborhoods getting tested, and that too before their eyes. Often it happens that the survey becomes an engaging exercise with mothers and fathers calling their children back from wherever they are in the village to be “tested” and onlookers and observers borrowing the “testing tool” and working with the children themselves. In the great deal of curiosity and discussion that takes place as ASER testing is being done in the villages, the parents for the first time become aware that their children may be lagging behind. This understanding of their children’s learning levels coupled with the widespread and large-scale participation and engagement by citizens everywhere is essential in promoting actions to influence change in education policy and practice from the bottom-up.

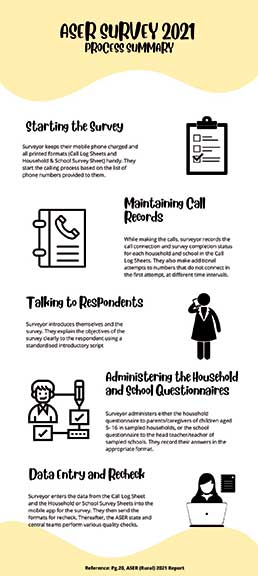

ASER Survey Process Summary – 2021 |

Learnings from ASER 2021

The possibility of following the basic learning level of cohorts on a nationwide scale as they move through the education system for a broad range of children starting as early as age five amongst others such as important trends in school enrollment is made available to India only via ASER’s cross-sectional data trends from every year. Considering the catastrophic effects wrought on by COVID-19 and its induced-school closures on children’s learning, the results of the last ASER (2021), conducted in September-October 2021, addresses the need for large-scale representative data. The survey completed by 76,706 households and 7,299 head teachers and teachers leaves one with questions reflective of our education system’s capability in handling the widening learning crisis as schools reopen after COVID and children come back with large learning deficits.

This is most notably highlighted in the shift observed in the enrollment pattern. The proportion of government school enrollment, across the board (age, grades, gender) soared to 70.3% accompanied by a fall in private school enrollment (25%). Especially after a period of prolonged school closure, this shift, marked with the influx of students, brings along problems and questions whether government schools and teachers are equipped enough to deal with the returning children’s large learning deficits and more broadly the learning crisis. Close to 75% of school teachers in reopened schools surveyed report following the curriculum of the current class and a high proportion of 92% of enrolled children across both government and private schools have textbooks for their current grade. Such an approach of following the curriculum will only exacerbate the problem, allowing for more children to fall behind and not surprisingly, a majority of children were reported to be having trouble catching up with the curriculum (65.4%). Supporting the ineptness of the school system is the large and growing tuition sector. The prevalence of paid tuition classes has increased across all the states and while the economic difficulties have driven the shift to government schools, parents are still willing to pay the money to have access to tuition classes.

Failure to address the widening cracks in the education system lies the failure of “schooling” and the whole system. As the interest in children’s learning outcomes grows, greater accountability and responsibility falls on the parents and the government to avoid the worsening of the learning crisis in the decades that will follow.

Research Team: Nupur Mathur, Likhitha, Priyanka Rambol and Harshita Gupta

Vignesh Krishnan currently works as the City Director with Teach For India, in Hyderabad. He leads a team of 100 educators directly impacting 3500 children from disadvantaged communities across in the city. He is a Chevening Scholar and holds a Masters in Education from University College London. He can be reached at vignesh.krishnan@teachforindia.org.

Ngawang Lhakey supports the research initiatives of Teach for India, Hyderabad as research intern. She has an undergraduate degree in psychology and is currently pursuing her Master’s degree. She can be reached at lhakeyngawang@gmail.com.

Isha Thakur is pursuing her bachelor’s degree in liberal arts from the University of Ashoka. She was a student in one of the Teach for India intervened classrooms in a Delhi government school and served Teach For All’s student advisory board as a member for a year. She can be reached at isha.thakur209@gmail.com.

Related Article