Living at the Edge of digital Imaginaries

Germaine Halegoua / University of Michigan

Over the past three years, I’ve been working on projects related to cultural geographies of digital media access and adoption, inequities in smart city development initiatives, and digital placemaking. All of these projects, compounded by the challenges and constraints of living with an ongoing global pandemic, made me acutely aware of the plurality of lived experiences of digital imaginaries. Pre-covid, I began research on a book related to dark fiber (for which I wrote a thought-piece for Flow) and expanded into an article with Jessa Lingel where we compared “failures of imagination” in urban broadband networks such as dark fiber and LinkNYC. When schools, daycares, and offices (as well as many other establishments) were closed due to the initial stages of Covid-19, I lived on the “rural side” of the digital divide, which intensified my experiences of place-based digital inequity, rural infrastructures, and “always off” connection. In 2020, I joined a research team at the Institute for Policy and Social Research (IPSR) to investigate Kansans’ experiences and perspectives on broadband connection across the state. Opportunistic and circumscribed imaginations of the past, present, and futures of digital connectivity reverberate throughout all of these projects. Those who develop, design, and implement infrastructures for digital connection imagine particular, emerging and potential uses and users for these projects, what connectivity means, where it is and where it isn’t, and who is included in digital futures.

Recently, I’ve been thinking a lot about the “edges” of these digital imaginaries and how living at these edges or seams shapes one’s relationship to place and feelings of belonging; particularly in the context of biased imaginations of the future of connected places and how we need to rethink the institutional processes of imagining these places.[1] As many scholars have continually shown, exploring and analyzing frictions, inequities, and failures of communication and listening that occur within digital imaginaries reveal the underbelly or shadows of socio-technical systems, biases, and persistent discriminatory attitudes, behaviors, institutions, and structuring logics (for some examples see the work of Ruha Benjamin, Safiya Noble, Sarah Hamid, Aimi Hamraie, Erin McElroy, Lisa Nakamura, and scholars affiliated with the Center for Critical Race + Digital Studies and the DISCO Network).

Through concepts such as discriminatory design, data justice, algorithmic and design justice (Benjamin 2019a, 2019b; Costanza-Chock, 2020) researchers have highlighted and critiqued the ways in which social biases are coded, re-coded, and decoded in the technologies of everyday life. Analyses of socio-technical imaginaries of technologies, policies, and media users have become increasingly prevalent in digital media studies and science and technology studies. More scholarship has focused on the ideologies and politics of platforms as they intersect with imagined futures of computing, and the ubiquity and differential harms of computation and algorithmic logics in everyday life.

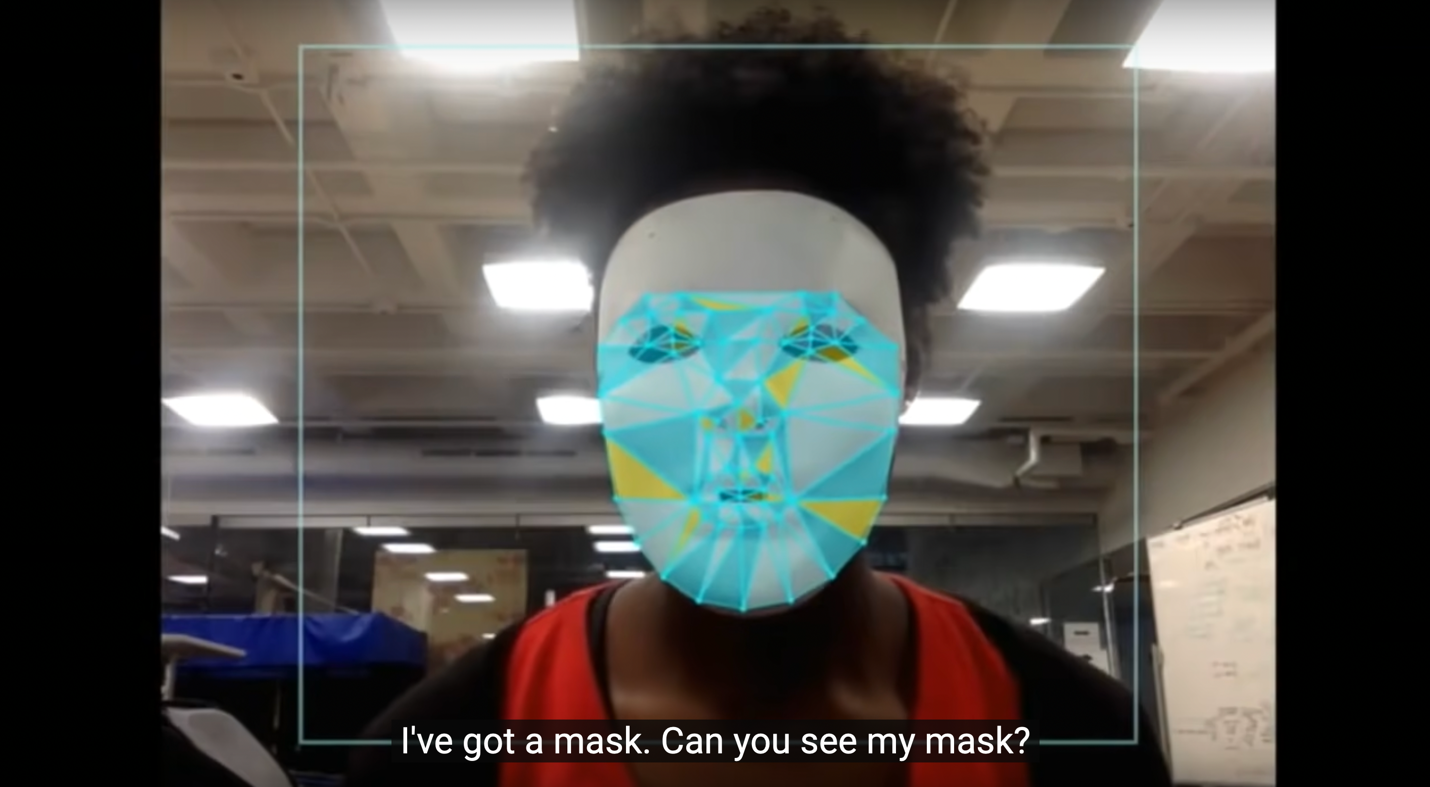

Scholars have focused on the perceived, lived, and affective experiences of these discriminatory socio-technical imaginaries as well. Actions and movements against these imaginaries are discussed at length, as are moments when discriminatory design is realized by those who are being discriminated against or those unimagined or mis-imagined in digital futures, and those who are continually oppressed or captive within these futures. One of these moments was reiterated in scholarly and popular press after computer scientist and founder of the Algorithmic Justice League, Joy Buolamwini, publicized the moment when she realized that machine vision, facial detection and facial recognition technologies couldn’t see or accurately read her face.

Equally important, and often underemphasized or under-investigated, are the moments where people realize they are living at the edge of “digital inclusion.” These moments occur when people realize that they’re just barely on the “other side” of a collective digital imaginary that doesn’t include them, or where they’re not considered “good users” (Gordon and Walters, 262). At the edges, discriminatory or selective decisions about digital connectivity are routinized in lived experience and are seen and felt through visible markers and manifestations that become nagging reminders of being undervalued or unimagined in digital futures.

In centering edges or seams rather than metaphors and relationships that indicate complete erasure or oppression, I want to recognize the material, ideological, and lived borders of exclusion. In these experiences and ontologies of exclusion, there’s some sort of effort or awareness toward digital inclusion or digital connection as a utility. The edge may indicate that certain populations and their situated or place-based problems and needs exist and might evidence previous or ongoing efforts to address issues of digital disconnection, equity, and access to resources, even if these efforts are performative. These performative inclusions are persistent problems as well, that serving certain populations and attending to their needs is superficial and not done in earnest. There’s a recognition of digital equity issues to be attended to, but there is also a palpable point at which these issues stop being meaningfully addressed and cared for or cared about by municipalities, ICT and telecom vendors, policymakers, or technology task forces. There’s an edge of attention, inclusion, and care.

These moments are often thought about as “failures of imagination” (which they are and I’ve used this term as well): failures to imagine all potential stakeholders and the plurality of ways digital media may be needed and used in urban and rural contexts; failure to imagine who has the right to intervene in the socio-technical production of place. Building on Sarah Elwood and Agnieszka Leszczynski’s (2022) “glitch epistemologies”, these edges are also productive moments to explore tactics for re-placeing spaces and honing tools for re-envisioning processes of digital inclusion. An example of living at the edge of digital imaginaries can be found in early controversies around the use of LinkNYC kiosks by unhoused or housing insecure populations, another in the original roll-out of Google Fiber in Kansas City. While there are many other examples to draw from, the example of rural internet access is particularly illustrative.

Over the past few years, I’ve had the opportunity to learn from Kansas communities about their experiences with broadband access. After reading and analyzing thousands of open-ended survey comments from people who routinely struggle to access reliable and affordable internet access at home, a common theme emerged. Many of the rural residents we surveyed and interviewed lived on the edge of someone else’s digital imagination. Many participants lived across the street or even a few yards from a fiber optic cable that bypassed their residence. One participant explained the unique frustration and stakes of living on the edge of material broadband infrastructure and the nagging potential for high-speed internet connectivity.[2]

“Fiber is available within three miles of our home, but the provider won’t bring it to us. That three miles is the difference between advancing my career (finding a remote job that I can do while living on the family farm) and falling behind.”

Participants were frustrated by the fact that they knew fiber optic cable was buried a few hundred feet from their house, they saw signs and traces of their presence and proximity every day, but adequate internet or broadband connection was not available at their residence and would possibly never be. The cost of extending the fiber lines were too expensive for the companies that owned them, and the population too sparse to obtain a return on their investment. As another participant explained:

“Fiber ends approximately one mile from our home. We know from employees working for that company that there is availability to hook into or extend that line. The cost per one household to pay for one mile is unrealistic. Yet, the opportunity for reliable, high-speed internet is so, so close. It is extremely disheartening.”

Fiber optic cables that bypassed their residences were a continual reminder that they were undervalued in past, current, and future imaginations of digital connectivity and that the imagination their (lack of) connectivity was subject to, was not their own. As another participant explained:

“I know there’s fiber within a half mile from our house, but nobody’s going to drag that half mile. Even though the functionality could be there, it just isn’t worth it for the major phone companies to do anything with it.”

Nick Mathews and Christopher Ali (2022) described these common experiences of rural residents living without broadband connections to their home as experiencing the “indignity of waiting” for more powerful actors to connect them. According to Mathews and Ali, rural residents who lack broadband access are “waiting in alternative ways” for household members to log-off, for off-peak times where web pages might load more quickly, for their turn to connect and be connected.

Participants in our study often spoke about these experiences of “waiting” as work. It wasn’t always in the waiting but in the attempt to connect that a conspicuous sense of power and powerlessness was felt. The recognition of the edge was profoundly felt through efforts exerted to extend or question the placement of that border. The constant visual reminders such as “do not dig” signs marking fiber optic cables or hills and forests that blocked line of sight networks revealed inequitable imaginaries as did the phone calls, meetings, and information requests to ISPs who noted the extraordinary expense of extending service lines a few miles down the road, or the long drives to fast-food parking lots, family members’ houses, and places of employment after hours. Through these time-intensive efforts, innovative and often expensive workarounds, living on the edge of digital infrastructures resembled the “digital edge” Watkins, et al. observe among Black and Latino youth, where socio-economic (and as evidenced here, geopolitical) conditions “give rise to distinct practices, techno-dispositions, and opportunities for participating in the digital world” (Watkins, et al, 2). Foundational to the social production and reproduction of these practices and dispositions is the recognition of the edge of imagination, and one’s relationship to the materialities, ideologies, and boundaries that edge maintains.

People are living on the edges or seams of digital imaginations (as well as at the oppressive underbellies) and researchers as well as municipalities, technology designers, and policymakers need better ways to communicate, listen to, and learn from these experiences and to be held accountable by communities for doing so. Policymakers and planners invested in digital access and infrastructure expansion and equity perpetually re-imagine and re-evaluate their initiatives. Recognizing these seams within future projects may shift digital imaginaries so that the same edges aren’t repeatedly re-inscribed in new ways.

Image Credits:

- Abandoned Google fiber installation in Louisville, KY

- Screenshot from Joy Buolamwini’s TEDx talk 2016 (author’s screen grab)

- Marker in rural Kansas indicating that fiber optic cable is buried along the roadside. The cables may serve residences on one side of the street and not the other or may bypass nearby residences entirely. (author’s personal collection)

Benjamin, R. (ed.) (2019a) Captivating Technology: Race Carceral Technoscience, and Liberatory Imagination in Everyday Life. Duke University Press.

Benjamin, R. (2019b) Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Polity Press.

Costanza-Chock, S. (2020) Design Justice: Community Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need. MIT Press.

Gordon, E. and Walters, S. (2016) “Meaningful Inefficiencies: Resisting the Logic of Technological Efficiency in the Design of Civic Systems,” in Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice, edited by E. Gordon and P. Mihailidis. MIT Press.

Halegoua, G. & Lingel, J. (2018) Lit up and Left Dark: Failures of imagination in urban broadband networks. New Media & Society, 20(12).

Leszczynski, A. & Elwood, S. (2022) Glitch epistemologies for computational cities. Dialogues in Human Geography.

Mathews, N. & Ali, C. (2022) “Come on f—er, just load!” Powerlessness, waiting, and life without broadband. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 27(6).

Watkins, S.C., Lombana-Bermudez, A., Cho, A., Vickery, J.R., Shaw, V., & Weinzimmer, L. (2018) The Digital Edge: How Black and Latino Youth Navigate Digital Inequity. New York University Press.

- Some of the ideas and text in this column are drawn from and elaborated on in “Re-placeing the Smart City,” a talk presented in May 2022 at the Beyond Smart Cities Conference in Malmo, Sweden. [↩]

- All participant quotes appear in Ginther, Donna K., Genna Hurd, Xan Wedel, Thomas Becker, and Germaine Halegoua, Kansas Broadband Study, sponsored by CARES Act Supplemental EDA Award for University Centers, forthcoming. [↩]

Policymakers and planners who engage in internet access, infrastructure growth, and equality programs are constantly re-imagining and re-evaluating their efforts. Recognizing these seams in future initiatives may modify digital imaginaries, preventing the same borders from being re-inscribed in new ways.

This was such a thought providing piece! I’m very interested in how this all will continue to reshape our perception of and relationship with the digital.